2021-9-14

Cathy Teng /photo courtesy of Chiang Cho-hung /tr. by Jonathan Barnard

中文版

In recent years, more and more young people are serving humanity by volunteering overseas, demonstrating that they too can lend a helping hand. Yet few also diligently consider the true meaning of volunteering. Having once had doubts about the need for volunteering, Dr. Chiang Cho-hung now aims to support sustainability and create solutions with his research as he moves beyond “cooperation” to “collaboration,” marching with others toward a collective future of global sustainability.

Chiang Cho-hung is a resident physician on the front lines at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital. As the Covid-19 pandemic has raged worldwide, in addition to busily making his hospital rounds he has also been submitting research results to medical journals, sharing the experience of Taiwan during the pandemic with the international community. He believes that all young people should use channels of their own to spread news about Taiwan to the world.

Out of their comfort zone

When Chiang was in elementary school, his family emigrated to Singapore. As a student there, Chiang was keen on international activities. He decided to return to Taiwan for his university education, enrolling in the School of Medicine at Fu Jen Catholic University. In his second year, he was selected to take part in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ International Youth Ambassadors Exchange Program. The members of his group had different professional backgrounds, but they worked together seamlessly, their strengths complementing each other.Chiang learned methods of cultural dissemination and was able to witness at first hand green energy and other technologies that supported the ethos of sustainability in different countries. “The youth ambassador program was the key that unlocked my global perspective,” Chiang says.

Fu Jen has a Tanzania-focused medical volunteer group that has been operating for many years. Each year the group recruits new members, who undergo special training throughout the school year before going to Tanzania in the summer for a month of service and study. In 2016, at the end of his third year in medical school, Chiang went to Tanzania as a member of the group. For fundraising purposes, the volunteers had to compose a written statement of what they planned to do in Tanzania. Even more important was discussing among themselves the medical assistance they could provide to Tanzanian tribal communities, as well as practicing putting on the public health education seminars they anticipated offering. “The work meetings during the planning period were quite intense.” With his experience as a youth ambassador, Chiang understood that teams such as these are much like a family. Living together, they need to support and believe in each other. Unafraid of challenges, they were able to realize their goals by working together.

Tanzania is in East Africa, and its eastern border is the Indian Ocean. Chiang describes how they flew for 20 hours, transferring planes twice, before landing at Kilimanjaro Airport, from where they drove for eight hours to reach their destination in Engaruka. The team lived in residents’ backyards, where they set up tents. “The living conditions for the local people meant that they had to generate their own electric power and fetch their own water, in which mosquito larvae were visible.” Having grown up in the age of the Internet and cell phones, he couldn’t help but add: “As you can imagine, there certainly wasn’t any Wi-Fi.” But getting through their nights with just the light of the moon and stars provided Chiang with an unforgettable experience.

Engaruka, which is ethnically Masaai, is geographically about the size of New Taipei City. But the entire district only had one doctor and two nurses. One of the goals of the group from Fu Jen was to improve the health of rural Tanzanian women and children. In this tribal community, the infant death rate remained stubbornly high, and the Fu Jen group in 2011 launched a plan to create an obstetrics ward for expectant mothers. In 2016, it had just opened for use. It puts pregnant women under the care of a doctor and nurses and allows them to get ample rest, clearing the way for smooth births. “There were two or three pregnant women at any given time in the ward when we were there, and there should be more and more in future years,” says Chiang, full of hope.

The true meaning of volunteering

As he recalls the details of his trip to Tanzania, Chiang suddenly blurts out: “In fact, I used to be rather opposed to volunteer work, and I wasn’t certain about the necessity of volunteering.” Before going, he had his share of doubts: “How do you go beyond just being a volunteer? How do we judge whether we are doing the right things?” These were questions that Chiang was asking himself back in his third year of medical school.

To explain his concerns, he cites an example: While in Tanzania he encountered a patient who was brought to the hospital because of a road accident. He was unconscious by the time he arrived. Medical personnel applied CPR, and nurses wheeled out an oxygen concentrator to try to save him, but the machine lacked a plug adapter, so everyone split up to look for one. After the machine was finally plugged in, the power supply tripped out. With the machine inoperable, they could only watch as the patient slipped away.

The incident bore witness to Tanzania’s lack of resources, and challenged Chiang to reconsider his preconceptions and avoid trying to provide what the Fu Jen group imagined local people needed, rather than what they actually needed. “After going to Tanzania, I came to better understand the value in volunteering. We all hope that one day local people will become self-sufficient and no longer need our intervention. Therefore, when it comes to working with them, we are emphasizing ‘collaboration’ more than ‘cooperation.’”

Both English words are typically translated with the same Chinese word, hezuo, but “cooperate” tends to emphasize that mutual benefits are bringing the parties together, whereas “collaborate” suggests that the two parties are building new values together and acting in support of a common vision.

“For instance, providing a maternity ward is a sustainable plan that can benefit local residents,” Chiang says. “Its operations can also be maintained by local medical staff.” When team members give residents checkups and discover that they have high blood pressure, they can adjust the health education they provide, emphasizing nutritional information and promoting steps to achieve a balanced diet. The patient data that they pass on to local doctors can provide guideposts for continued care. Small steps can have a long-term impact. “It was only by integrating sustainable development goals into what we were doing that I was able to truly understand the meaning of volunteering. I realized that it can include so very much.”

Big things from small steps

Curious to explore the background to issues, upon returning to Taiwan from Tanzania Chiang joined the medical research team at National Taiwan University, hoping that research would answer his own questions. “For instance, do maternity wards actually lower mortality rates? Do health checks benefit local residents? These are questions that require research and data analysis from a public health perspective,” says Chiang.

In March of last year, as the Covid-19 outbreak began to spread around the globe, the World Health Organization was only recommending social distancing, but not suggesting that people wear face masks around each other to reduce the spread of the virus. But as a result of Taiwan’s previous experience with the SARS epidemic, people here soon began wearing masks on their own initiative, and the government likewise showed foresight in quickly setting up a national mask taskforce, taking control of mask production and rationing the supply. These steps gave everyone access to masks with which to reduce the spread of the virus. They helped Taiwan to maintain control over the epidemic for a year.

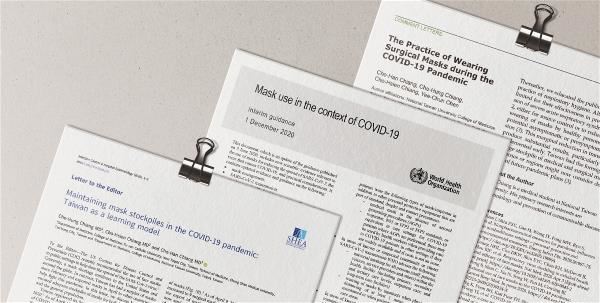

Chiang has compared the pandemic’s development in Taiwan and Singapore, concluding that masks are an effective means of infection control. The journals Emerging Infectious Diseases and Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology published his research results, and he received inquiries from a New York Times reporter asking for more details about disease control efforts in Taiwan. In June of last year the WHO updated its policy recommendations for epidemic control, calling for both social distancing and the wearing of masks. The guidelines that the WHO published in December 2020 cited Chiang’s papers.

“As global citizens, we ought to use different channels to share our successful example with other countries, so that when they are uncertain about what to do, they will at least have a basis for action and not be at a complete loss,” says Chiang Cho-hung. Getting these data widely disseminated will allow more people to understand the facts, so that more people can be protected. In an era when viruses can spread rapidly around the world, doctors’ professional responsibilities are perhaps no longer limited to treating the patients in front of them. If they can communicate more freely with the international community and not be reticent in sharing their research results, then even young doctors such as Chiang can provide a spark for the global public health community.

Article and photos courtesy of Taiwan Panorama September 2021