2025-11-28

(Courtesy of Taiwan Panorama November 2025)

Chen Chun-fang /photo by Kent Chuang /tr. by Phil Newell

“Taiwan warriors, hoooo, hoooo! Hero! Hito!” “Tell the world, Team Taiwan! Whose house this is, Team Taiwan!” During the 2024 World Baseball Softball Confederation Premier12 baseball tournament, the world was rocked by waves of cheering for the Taiwanese team. For many foreigners encountering Taiwan baseball for the first time, this was a real culture shock.

It is a midsummer afternoon in Taiwan, and before the game has begun the area outside the stadium is filled with fans. Some are wearing baseball shirts and caps, while others are holding team cheering fans, towels, thundersticks, or even their own handmade props as they eagerly await the start.

A stage for enthusiasm

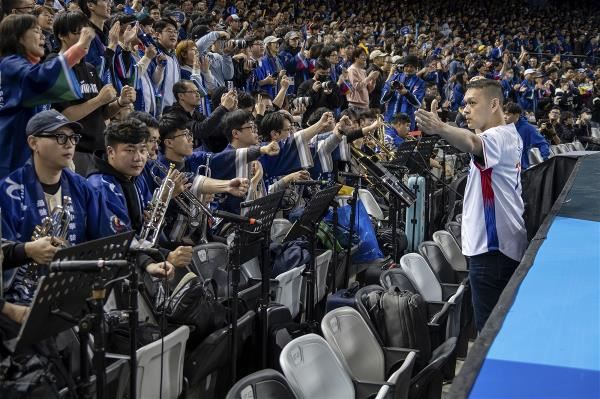

“One more strike!” “Strike him out, strike him out!” “We invite all of you, the Fubon Guardians family, to dance along with us!” On a platform in front of the infield seats, Travis, the head cheerleader for the home team Fubon Guardians, energizes the crowd with his voice and gestures. In combination with the cheerleaders dancing next to him and the dynamic music, he stirs up support for the team. Travis says: “We’re like a USB port, responsible for conveying positive energy, while the fans use their voices to transfer this energy to the players, and the players respond with their on-field performance. This resonance among the three is at the core of Taiwanese-style cheering.”

Every detail is carefully arranged to optimize the game-watching experience. Next to the field, there are eateries serving all kinds of Taiwanese cuisine as well as souvenir shops selling peripheral merchandise, giving the fans a chance to stock up on whatever they need. On days off, teams organize themed events, such as the “temple festival” organized by the Uni-President 7-Eleven Lions. It brings temple culture onto the baseball diamond, including setting up a “Tainan Lion’s Roar Temple,” staging Taiwanese Opera performances, and holding a “Lion King Palanquin” procession, thereby generating a fun atmosphere for fans.

Between innings, many teams have their mascots lead kids in on-field dance routines. Watching them step out with confidence and show their love for baseball has become a highlight that families look forward to.

Chen Tzu-hsuan, a professor in the Graduate Institute of Physical Education at National Taiwan Sport University, points out that sports competitions are a form of performance media. Compared to other types of performance with prewritten scripts, such as theater, the biggest difference with sport is its real-time action and the collective responses and feelings of the crowd. When watching a game at a ballpark, besides seeing who wins and who loses, fans introduce their own emotions onto the field through team fight songs, chants, and rituals. Games become venues for emotional release and collective participation, with the happy ambience resembling a carnival. “The minute-to-minute highs and lows of sport, and the shared euphoria when the game ends, make it unlike any other form of entertainment,” says Chen.

Team fight songs

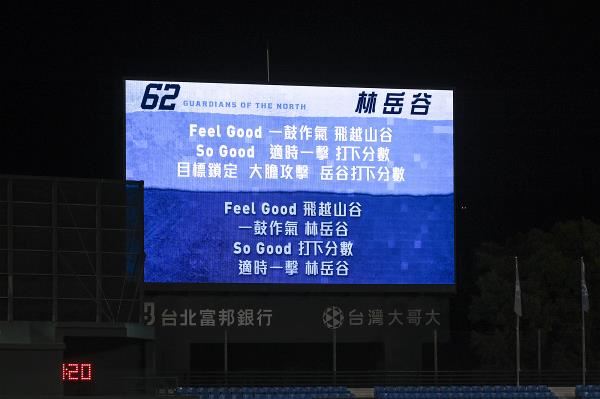

The most intriguing aspect of Taiwanese-style cheering is undoubtedly the team fight songs with which all fans are familiar. Every player has his own particular tune, and the sound of a song’s intro tells fans whose name to cheer. When there are men on base with a “run-scoring opportunity,” the spectators collectively sing the team’s “chance song,” raising the energy level in an instant.

Yü Chin-chin, a longtime musician in team support bands and musical director for the national baseball team, notes that early on team support equipment was rudimentary, with just a man with a megaphone accompanied by a drum and a few horns. Most team fight songs were pop tunes, cover songs, or anime scores, and it was enough that they were easy to conduct for the bandleader and easy to play for the musicians. But these days team support is markedly different. It is routine for teams to invest a lot of money into setting up equipment and hiring head cheerleaders, cheerleading squads, and mascots. Most team fight songs are original compositions, with teams competing in terms of number and style of tunes. The result is that Taiwan team fight music is abundant and diverse.

These songs not only need to have catchy rhythms, but more importantly must be able to motivate fans. There are different arrangements for everything from game opening anthems and the tunes played when players go on-field, to relaxing danceable numbers played between innings and the “ending songs” played following a win or loss. Creating and maintaining the right atmosphere or building up enthusiasm depend on the long-term experience and chemistry of the leader and musicians. This kind of precision enables spectators to feel as if they are attending a musical banquet.

The wordplay of Taiwanese cheers

Between songs, the head cheerleader invites the fans to shout slogans. Simple yet impactful and richly creative wordplay is a defining characteristic of Taiwanese-style cheering.

Chen Tzu-hsuan notes that there is a particular fondness for word pairings in Taiwanese-style cheers. This fact is connected to the diverse linguistic background in Taiwan, where many languages—including Mandarin Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese, English, and even indigenous tongues—are widely spoken on a daily basis, creating more opportunities for wordplay. For example, teams often use longstanding chants such as one in which the Taiwanese word for “boxed meal” (piān-tong, from Japanese bentō) is paired with the Mandarin for “swing and miss” (huībàng luòkōng); one in which the Taiwanese for “mochi” (muâ-tsî, from Japanese mochi) is paired with the Mandarin for “strikeout” (sānzhèn chūjú); and another in which the Mandarin for “fruit marinade” (shuǐguǒ lǔwèi) is followed by the English “double play.” These call-and-response pairings mix Taiwanese, Mandarin, and English to create diverse cross-language sound matches and rhythms, thereby enriching the possibilities for wordplay.

Another example is the signature cheer for the Paiwan professional baseball player Giljegiljaw Kungkuan. “Clap clap clap—Gilje! Clap clap clap—Giljaw! Gilgegiljaw Kongkuan kisamulja!” This deftly combines the syllables of his name with kisamulja, the Paiwan word for “work hard” or “keep it up”—roughly “Let’s go!”—to form a cheer that is uniquely personal and also rich in cultural content.

Emerging from a low ebb

Looking back over the development of the Chinese Professional Baseball League (CPBL) in Taiwan, Taiwanese-style cheers have undergone several transformations. Early on most cheers were organized by groups of fans themselves, such as the “Flying Knives Group” who supported former player Chen Yi-hsin. They used very direct chants filled with grassroots energy to manifest the fan culture of the early days of pro ball in Taiwan.

At the first CPBL game, played in 1990, the main cheering approach was to use bands organized by the teams to inspire fan yells and shouts. Many people share memories of the piercing quality of brass instruments combined with the roaring of the fans. However, in 1996 the league was rocked by a number of game-fixing scandals and the enthusiasm of the first generation of fans waned, leaving stadiums virtually empty for a while.

It was only in 2010 that things turned around. At that time the Lamigo Monkeys (now the Rakuten Monkeys) introduced Korean-style electronic music, igniting the passion of a new generation of fans. The loud, thumping electronic music, matched by the dancing of cheerleading squads, created new visual and auditory stimuli, and all the teams followed suit. Fans have since then hotly disputed which is better: Korean-style electronic music or Japanese-style bands.

Yü Chin-chin says that electronic music can quickly energize the atmosphere in a stadium and offers diverse styles. However, wind instrument bands have warmth and depth. “As bands grow larger, the music can transition from a single line to polyrhythms and harmonies, enhancing its layers and power and directly penetrating people’s hearts and minds.” He argues that the main challenge for the future is to find a balance between the diversity of electronic music and the distinctiveness of live bands.

Chen Tzu-hsuan mentions that Taiwanese-style cheering shares many things in common with Taiwanese culture in general. Both are “a combination of foreign elements with local characteristics” that have created the Taiwan that we know today. Despite the period of public disdain suffered by the CPBL, baseball fan culture never disappeared, and has found a new outlet through contemporary cheering. Chen declares: “The most impactful thing in sports is still human voices.”

Chen shares the experience of the 2024 Premier12 tournament, when Taiwanese gathered in large numbers at the Tokyo Dome to shout powerful and compelling slogans like the “Taiwan warriors!” chant mentioned above. It is precisely this Taiwanese-style passion that is such a novelty to foreigners, and Yü Chin-chin extends the following invitation to international friends: “Come to Taiwan and watch a CPBL game, and you will discover that cheering can be soooo different.”