2025-4-15

Courtesy of Taiwan Panorama March 2025

Cathy Teng /photo by Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation /tr. by Brandon Yen

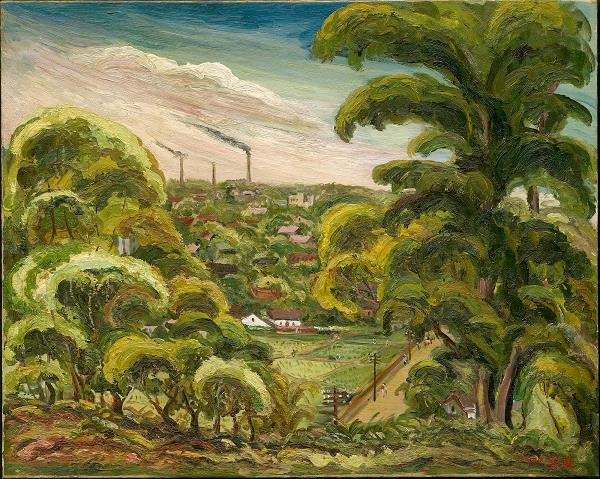

In Looking towards Chiayi (1934), Chen Cheng-po (1895–1947) gazes lovingly at his hometown, capturing a highly charged moment of meteorological change. Familiar though it may be to locals, the volatile weather depicted in this oil painting is actually very rare in other places on the Tropic of Cancer.

To celebrate the 130th anniversary of the painter’s birth, the Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation has joined forces with the National Taiwan Museum, Hung Kuang-chi (associate professor of geography at National Taiwan University) and his 407 Forestry Studio, and Microcosms Museum Creatives to present an exhibition that features eight of Chen’s original works. Entitled Rediscovering Taiwan, the exhibition explores what these paintings tell us about our islands from the perspective of natural history.

Natural history

“Taiwan is where three climate determinants—the Kuroshio Current, the Tropic of Cancer, and the monsoons—converge.” The geographical leitmotif of the exhibition comes from Chen Li-po, eldest grandson of Chen Cheng-po and chairman of the Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation. Years of studying his grandfather’s paintings reinforced Chen’s environmental consciousness, which quietly beckoned to him and eventually took shape as a curatorial project.

“This is a precious opportunity for us to use the works of a Taiwanese painter to interpret local stories with regard to human geography and physical geography,” Hung Kuang-chi says.

The concept is new and fascinating, but forging connections proved to be a formidable challenge—until Hung lit upon an interview dated 1932 where Chen Cheng-po said: “What I always try terribly hard to express is the ontology of nature and of physical objects. That’s the first thing. Secondly, I ponder, refine, and distill images that are projected within my mind, capturing those moments that are worth delineating. The third is that each work has to have something to say.”

Using this revealing statement as a peg to hang the exhibition on, Hung tells us that Chen’s modus operandi resembles that of a naturalist: he loved to work en plein air, observing and depicting nature. The exhibition treats Chen’s paintings as sites where naturalists gather samples to study, endeavoring to reconstruct the fleeting moments that the painter wished to capture, to investigate the natural forces that shaped each painterly scene, and thus to bring Taiwan’s ecological diversity to the foreground.

Where art meets nature

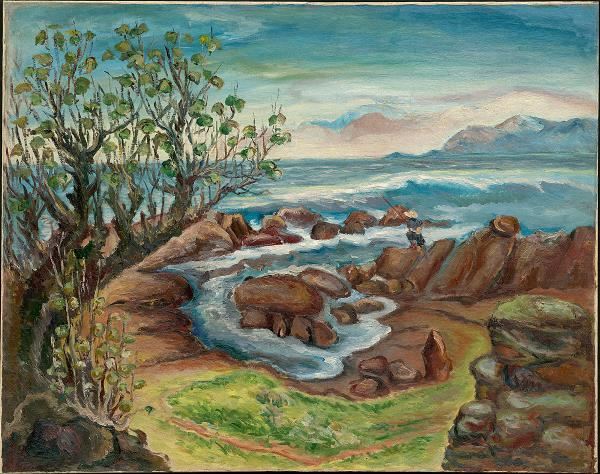

Chen’s Crashing Waves (1939) marks a breakthrough in this dialogue between art and nature. Hung, who has an academic background in forestry, is able to identify the large plant in this oil painting as a sea hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus). Because the tree is not in flower, he assumes that this is a winter scene. Furthermore, the Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation indicates that the seascape portrayed here was at Cape Bitou in New Taipei’s Ruifang District. These clues, Hung explains, come together to provide compelling context for the human figure enjoying the pleasures of rock fishing in the painting.

This scene depends upon the combined forces of monsoon winds and the warm waters of the north-flowing Kuroshio Current. Each year, the moist northeasterly winds facilitate the growth of sea lettuce on the rocks in this northeastern corner of Taiwan, while the Kuroshio Current serves as a highway for marine life, bringing shoals of fish to the vicinity of the cape, where they feed on the rich nutrients in the waters. Crashing Waves orchestrates the powers of land, wind, and sea, turning the spotlight on humanity’s joyful response to nature. “It was this painting that gave us confidence. We began to feel that we could come up with a new narrative,” Hung says.

The Northern Tropic and the monsoons

Hung draws our attention to one of Chen’s earliest oil paintings, Tropic of Cancer Landmark (1924), and his masterpiece of 1934, Looking towards Chiayi. Both works focus on extraordinary atmospheric phenomena.

Hung begins by explaining the reference to the Tropic of Cancer. The Northern Tropic and its Southern Hemisphere counterpart, the Tropic of Capricorn, mark the northernmost and southernmost latitudes at which the sun may be seen directly overhead. Our ancestors observed the heavenly bodies and saw that the sun reached as far as the constellations Cancer in the north and Capricorn in the south before traveling back toward the equator: the word tropic comes from the Greek word for “turn.” The regions between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn receive abundant solar energy and are referred to as the tropical zone, or tropics. In Western cultures, the tropics carry both positive and negative connotations—fecundity and savagery.

In 1895, Japan acquired Taiwan through the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and in its subsequent governance of the island it followed the paternalistic example of the Western colonial powers. Born in Taiwan, Chen Cheng-po first made a name for himself in mainland Japan. He set out to counter the prejudicial views of the tropics that underlay such colonial rule.

Chen’s Tropic of Cancer Landmark portrays a monument in Chiayi that marks the position of the Northern Tropic. However, rather than an arid landscape, in the background we see a gathering thunderstorm, the likes of which locals would expect to encounter on summer afternoons. Hung says that desert climates reign in many other places situated on the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. But Taiwan boasts a lush environment, thanks to a monsoon system which formed as early as 8 million years ago. The southwesterly and northeasterly monsoon winds bring considerable rainfall. During the rainy season in late spring and early summer, these monsoons meet over Taiwan and produce a persistent weather front that causes what is known as the “plum rain.” The rain that comes with typhoons in summer and autumn further serves to nourish our flora and fauna.

Meteorology

The foreground of Looking towards Chiayi abounds with greenery, but the clouds in the background hint at the impending arrival of a typhoon. To verify the weather conditions when Chen worked on this painting, the Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation consulted a pencil sketch of Chen’s, dated August 21, 1934. Chen Chia-chi, a technical specialist at the Central Weather Administration’s Southern Region Weather Center, helped access details of the weather in late August of that year. Sure enough, the weather charts show a low-pressure area over the sea near Southern Taiwan, and a typhoon approaching the island from the southeast. According to meteorological data gathered over the course of more than a century, on average Taiwan is affected by three to four typhoons each year. The scene depicted in Looking towards Chiayi “is one that happens right before a typhoon arrives,” Hung says. “The sky appears tranquil at first glance, but there are quiet agitations in it.”

Hung draws a comparison between Chen and Instagram users who share images of strangely colorful skies in the immediate lead-up to a typhoon. “Chen didn’t just dream up the scene. He was exploring what the sky was really like before a typhoon arrived.”

Chen’s paintings reshape the cultural discourse of tropicality by celebrating Taiwan’s natural bounties and the benign influences of our distinctive climate systems. In doing so, they tell us how Taiwan came to be blessed with such startlingly exuberant greenery.

Seas of clouds

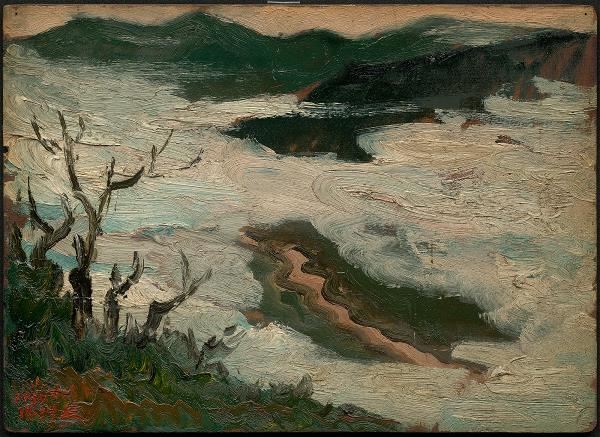

Chen’s Sea of Clouds (1935) and Accumulated Snow on Jade Mountain (c. 1947) bring us to loftier regions. The former captures a landscape that Chen saw when he traveled by railway to the towering mountains of Alishan and hiked to Zhushan. Hung says that for mountain hikers, “seas of clouds constitute an integral part of their experience of Taiwanese mountains.” Friends who are avid mountain hikers have told him that these phenomena are actually very rare in Japan. “Taiwan is constantly under the influence of monsoon winds. The densely forested Central Mountain Range and Xueshan Range, both of which follow a north–south orientation, have smaller mountain chains branching off their eastern and western flanks. Seas of clouds form when the monsoon winds hit these mountains. Hence the belts of cloud forests that we know so well.” It was these special environmental conditions, Hung adds, that gave birth to the Taiwan red cypress (Chamaecyparis formosensis) and the Taiwan yellow cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa var. formosana).

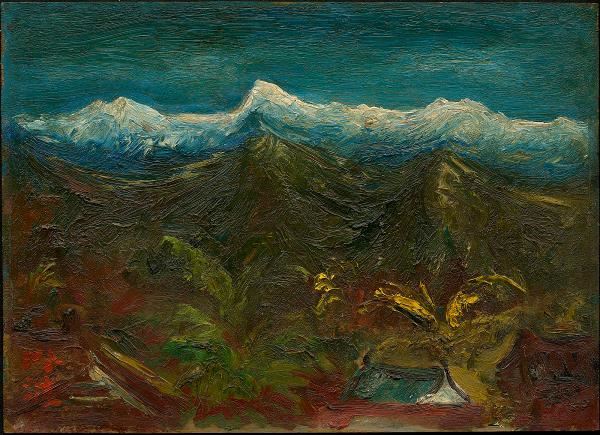

Accumulated Snow on Jade Mountain highlights another of Taiwan’s distinctive characteristics. The island came into being because of the convergence of the Philippine Sea Plate and the Eurasian Plate. Plate tectonics here created 285 mountains more than 3,000 meters tall, packed within an area of just 36,000 square kilometers. “This topography, combined with the monsoon winds and Taiwan’s location on the Tropic of Cancer, accounts for a great diversity of vegetation zones. Within a short distance you encounter very different plant communities at different elevations, as if you were traveling from tropical to subtropical and temperate regions.” From the tropical banana trees in the foreground to the temperate forests and snow-capped peaks in the distance, Chen’s painting offers a lesson in altitudinal zonation. In Japan, Hung says, we’d have to travel all the way from the Ryukyu Islands to Hokkaido to see such a variety of plant life.

Taiwan in transition

Other scenes that captivated Chen concern changes in rural communities, and the impact of government policies on the indigenous peoples. These can be observed in A Farming Household (1934), Mountain Living (1930s), and East Taiwan Coastal Road (1930).

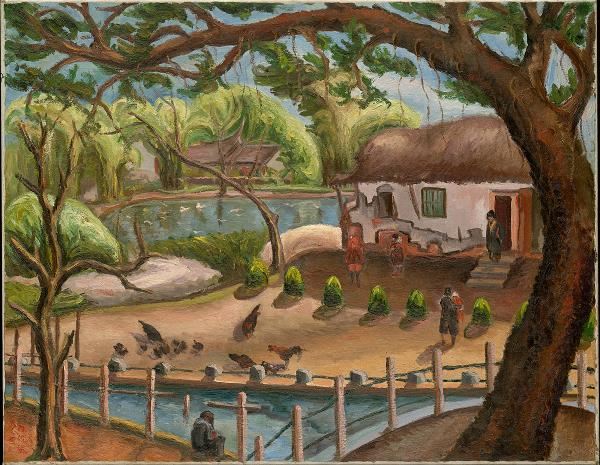

A Farming Household depicts a scene in Changhua, which has abundant groundwater. Hung reads this watery landscape through the lens of a scheme launched in 1934 by the Japanese colonial government to improve conditions in rural areas across Taiwan. Chen’s painting encapsulates the process whereby the wildness of traditional agricultural landscapes was being tamed: the trees have been pruned, and railings have been installed along a neatly laid-out water channel.

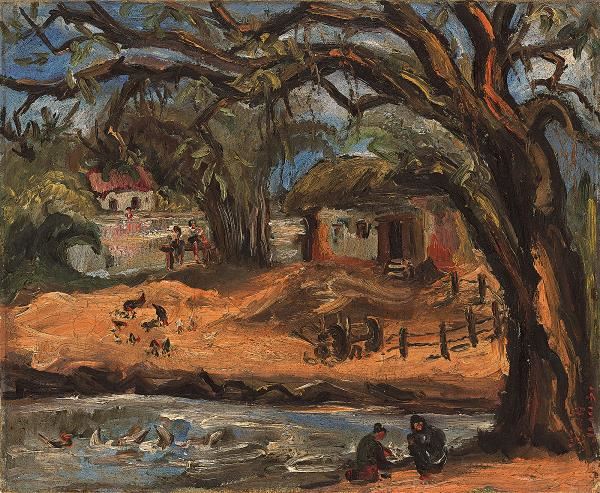

Chen’s Sunset at Song Village (1932) portrays the same locality, but the brushstrokes are a good deal less restrained, and the colors are richer, bringing into focus the raw vitality of traditional rural life. “By juxtaposing the two paintings, we can tell that Chen was documenting a landscape in transition.”

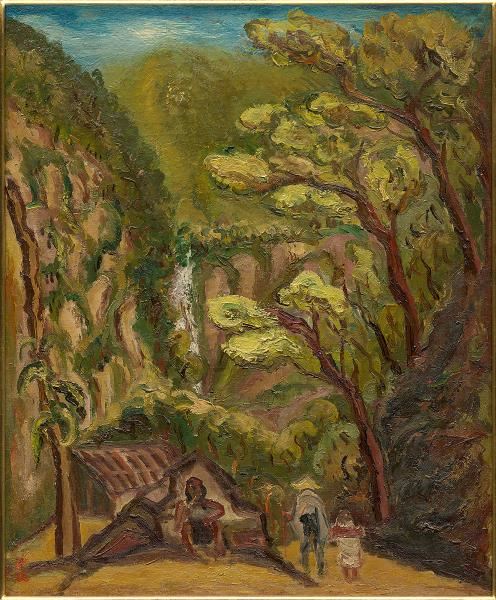

Among Chen’s few works on subjects relating to Taiwan’s indigenous peoples are East Taiwan Coastal Road and Mountain Living. The former depicts an indigenous settlement in Hualien, a mother and her child walking on a coastal road, and Chongde Gravel Beach, which can still be visited today. Rather than employing one-point perspective, the painter uses multiple vanishing points to construct a sense of space. Also inspired by Eastern Taiwan, Mountain Living shows similar compositional elements. Here Chen records a time when people still dwelled in Inner Taroko. The deliberately disproportionate renderings of the mountains and of the indigenous and visiting human figures once again remind us of Chen’s view that each painting should convey something meaningful.

Shortly after Chen finished Mountain Living, Taroko was designated as a national park by the Japanese colonial government. Hung tells us that this official recognition set in train the establishment of local amenities and facilities, while media coverage led to an increase in visitor numbers, gradually altering the appearance and character of Taroko. The process of transformation engrossed the attention of Chen and other intellectuals of the time, and the memory of that transitional period is forever enshrined in Chen’s painting.

Placing Taiwan

The Chen Cheng-po exhibition at the National Taiwan Museum crosses disciplinary boundaries. Hung emphasizes that the project has been made possible by the inputs of various specialists, whose different perspectives contribute to a richly diverse understanding of Chen’s vision of Taiwan.

Many meteorological, geographical, cultural, and natural factors conspire to make Taiwan what it is today. Blessed with the Kuroshio Current off its eastern seaboard, and nourished by the monsoon winds and benign weather conditions around the Tropic of Cancer, Taiwan is able to sustain the lives of the tremendous abundance of different species that flourish here.

The next time someone asks you where Taiwan is, you might want to tell them: It’s where the Kuroshio Current, the Tropic of Cancer, and the monsoon winds meet.